Tibet today has gradually become less Tibetan. Tourists from far away are often disappointed; people have been saying that “Lhasa is the clone of Chengdu.” I counted once that within the distance of one hundred and perhaps a few more meters from my family home in the New Shol Village behind the Potala to the entrance of the nearest street, I totally ran into 37 Han Chinese and 5 Tibetans. The increasing immigrants are apparently an important reason for Tibet’s change.

Tibet today has gradually become less Tibetan. Tourists from far away are often disappointed; people have been saying that “Lhasa is the clone of Chengdu.” I counted once that within the distance of one hundred and perhaps a few more meters from my family home in the New Shol Village behind the Potala to the entrance of the nearest street, I totally ran into 37 Han Chinese and 5 Tibetans. The increasing immigrants are apparently an important reason for Tibet’s change.Can Tibetans resist such a heavy wave of migration? The answer is undoubtedly pessimistic. We live on our own land but are not the ones in charge of this land. Tibet has been ruled by a supreme power for the last half century. The difference between us and the supreme power manifests not only through military and economic forces. Solely in terms of the population, how can 6,000,000 Tibetans compete with the Han Chinese population which is 200 times larger than us? Therefore, ideas of violent resistance would not make any more difference than throwing eggs at a rock. It might appear brave and tragic, but would not help alter the overall conditions we are facing.

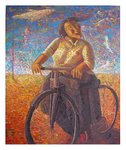

However, no supreme power is absolutely irresistible. The power of resistance in fact exists in our traditional culture. I have in Amdo seen a mural painting in a monastery. On the painting, the helmeted soldiers of justice are opening fire toward their enemies. The bullets shooting out of these soldiers’ weapons turn into flowers. How should these flowers blooming on the wall of the monastery be understood? -- They symbolize the compassion and wisdom embedded in the traditional Tibetan culture.

Yes, our traditional culture is our single weapon.

Historically, the iron hoofs of the Mongolian army conquered a large part of the world. All of China was defeated; Chinese had to hand over their imperial dynasty to the Mongolian rulers. On the contrary, why, instead of being conquered or destroyed by the valiant Mongolians, did Tibetans become religious teachers of them? Why have Tibetans and Mongolians remained brothers to each other to this day?

If our Tibetan tradition had been able to tame Mongolians in the past, why couldn’t it pacify the contemporary Chinese?

It is worth remembering that the Han Chinese have long believed in Buddhism. Although the size of the Chinese Buddhist population might be smaller than the Tibetan one, and although it is common for Chinese Buddhism to be mixed with superstitions and mundane motivation of the believers, the religion has after all spread widely and remains very influential among the Han Chinese.

Therefore, because of its well-preserved lineages, its rich and colorful rituals, its fully developed philosophical foundations, and its incredibly attractive artistic expressions, Tibetan Buddhism is able to convince many Han Chinese. In fact, while it is a common scene in Lhasa that Chinese migrant laborers worship and make their offerings in the monasteries, the elite population in China has just begun to feel their need for the religion.

Tibet has long become a fancy attraction in international society. Under the leadership of the Dalai Lama, the Tibetans who were forced into exile have brought Tibetan civilization into the larger world. “Tibet Fever” and “Fever of Tibetan Culture” that have been so popular and even become a fashion are the contributions of the exiled Tibetans. Such a fashion has then turned around to attract the Chinese elites. While they are “hooked up” with the international trend, they also have began to be “connected” with Tibet. Among the non-stop immigrants who have entered Tibet, some deserve more of our attention. The interest of these immigrants in Tibet is due to their interest in Tibetan culture; their expectation for Tibet is because of their expectation for Tibetan culture.

In Tibet, I became friends with many Chinese of this kind. One of my friends wrote about how he felt after his first encounter with Tibetan civilization: “It is a thunderstorm-like shocking and a muteness.… It is a natural reaction when my presumptuous cognition is abruptly overturned by the different civilization that I have just met.” Having heard the laughing coming from the tents of Tibetans on a stormy night on Mount Everest (Jhomo Langma), another friend concluded: “One day when only one people and their civilization is left on the earth, it has to be the Tibetans and their ancient civilization that emphasizes the oneness between nature and culture.”

A nation’s culture begins to gain strength when it can hold onto its own fundamental attributes, when these attributes are lasting without interruption, and when they are down to earth and not falling into nihilism. Would such strength be sufficiently respected by others? Would such strength provide us enough protection and even help us defend against the supreme power? These concerns are relevant to everyone in the nation.

Let’s insist on the cultural tradition of ourselves – instead of accepting the authoritarian domination of the totalitarian regime, instead of running after the materialistic currents of the modern world. A combination of these two factors would be a strong damaging force which could directly pierce into the soul of the Tibetan nation.

Let’s insist on the cultural tradition of ourselves. I am neither encouraging ignorance nor promoting conservativism. Instead, I am talking about a cultural choice – particularly among the elite Tibetans. All of the intellectuals, professionals, monastics, and officials should take upon themselves to become the role models for average Tibetans, to educate the latter that the “benevolent gifts” from the supreme power are not necessarily good, and that running after materialism will not necessarily bring us joy or satisfaction. Instead, we should walk on our own path.

Let’s insist on the traditional culture of ourselves. This principle should be applied to the details of our everyday lives and to every aspect of our spiritual lives. Although it is not very convenient to go to work in the Tibetan clothes that have derived from the nomad culture, we should still wear them in our offices. Although it is not an easy task to communicate in Tibetan in the midst of 1,200,000,000 Han Chinese, we should still keep speaking the language, which functions to preserve our memory of history. We live in Tibetan houses. We celebrate Tibetan holidays. At home, we hang thangkas, light butter lamps, and invite Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and lamas in burgundy robes to accept our reverence. Even though we do not have the power to hinder the Chinese government’s railroad construction and their mining and other developments, we can at least restrain ourselves from building hotels, restaurants, and shops of the Chinese style, and from the Chinese way of using gambling, KaraOke, and Han or Tibetan prostitutes to attract customers and tourists.

We should not use flatteries to exchange immediate economic interests. If the Han Chinese want to come to our place, sorry, they must behave in accordance with the Tibetan manners. They should respect what we respect, and honor what we honor. In this way, they would be forced to become cautious and careful about their conduct. Therefore, even if it might sound very artificial, we should still try to produce a thick Tibetan cultural atmosphere.

This is indeed a cultural choice. We don’t have other options besides it, because we are on the weaker side when it comes to a comparison of material power. This is a reality.

We can otherwise be more open-minded in importing foreign formulae, accepting new things, and nurturing more diversified ways of life in our indigenous land. However, because we are on the weaker side and nothing too much has survived after the damage done to us, we have to insist on everything in our culture and tradition. No matter how small these things might appear, we have to make efforts to ensure that they are not going to be washed away by the overwhelming waves.

In fact, we should be full of confidence, because our cultural tradition remains illuminating after so many hardships and stormy struggles. As one of my Chinese friends has said, “The remedy that can cure illness and diseases in the world remains hidden in Tibet.” Our culture and tradition is exactly the remedy. If we don’t value it, how would it be able to treat the also sickened Tibet? If we ourselves have given up and only know how to imitate and chase profitable opportunities, Tibet will be saturated with various “clones” from inland China. Eventually, we would become strangers in our own land.

There is no reason for us, that is, for every Tibetan, to become just like the Han Chinese or any other people. Although today’s world is undergoing “globalization” and becoming a so-called global village, if we want to have a seat in the village, to join the diverse community but maintain our unique character, to win over our rights, to have our voices heard, and to be ourselves, we have only one choice which is to insist.

If we still care about Tibet’s existence, we have to insist on our Tibetan cultural tradition. Under the circumstances, we might not be able to get rid of Chinese rule. However, it is totally possible for each Tibetan to insist on our culture. Don’t complain about the environment, don’t withdraw from our responsibilities, let each of us start from ourselves – to insist. This is the hope we can pass on to future generations.

3/10/2005 in Beijing

No comments:

Post a Comment